At Home, At Work, And In Between

- March 16, 2013

- / Category Ritual

- / Posted By admin

- / Comments Off on At Home, At Work, And In Between

In the recent debate over the decision by CEO Marissa Mayer to revoke permission for Yahoo employees to work at home, there has been much discussion about whether people are as productive when they work at home as when they work at centralized, corporate-owned offices. Some have contended that work at home is more productive, while others have argued that employees are most productive when they are located within a specifically designated office. Few in these discussions, however, have paused to consider whether there is a difference in the qualitative nature of productivity in a home office in contrast to productivity in a separate office environment.

The idea of a home office can seem like a contradiction in terms to those who take seriously the state of mind that an office represents. The word “office”, after all, derives from the same root as the word “official”. An office is supposed to be a location where people devote themselves to an well-established external system, conform themselves to its rules, and act according to duty, rather than to their private impulses.

A home, in contrast, is commonly regarded as the place where people are best able to express their authentic selves. In the home, people follow their own rules and create their own systems for doing things, working in their own employment. This home attitude is the opposite of the ethos of the office, so how could a home office ever serve as a place where serious work, like that done in an office building, can be accomplished?

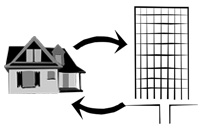

The distinction we make in our commercial-industrial culture between home and work identities is manifested in the very placement of our homes, typically far away from where we work. We could save ourselves a great deal of trouble if we chose homes located close to our offices, but most of us do not. We prefer to keep our work and home lives distinct, accentuating a separation of identity through a physical separation. The distance we must travel in between the home and the office becomes a ritual symbol of their distinctiveness. We keep both identities intact by keeping them far apart.

The distinction we make in our commercial-industrial culture between home and work identities is manifested in the very placement of our homes, typically far away from where we work. We could save ourselves a great deal of trouble if we chose homes located close to our offices, but most of us do not. We prefer to keep our work and home lives distinct, accentuating a separation of identity through a physical separation. The distance we must travel in between the home and the office becomes a ritual symbol of their distinctiveness. We keep both identities intact by keeping them far apart.

The separation of a person’s psychological sense of self into distinct at-home and at-work identities is a ritual act that is among the most fundamental aspects of our ritual-industrial culture. The idea that people split their lives into domestic and professional aspects is so central to our culture that, as adults, we take it for granted. For adolescents, of course, the arrangement does not feel at all natural at first, and the resolution of the anxiety sparked by the need to create a distinct professional identity is one of the most common themes of coming-of-age struggles in commercial-industrial societies. The conflict between the demands of the home identity and the work identity never truly go away, of course, but are managed through a series of daily rituals that create psychological distance between work and home.

Prime among these rituals is the daily commute. People may not consciously decide to live far from their places of work so that they can engage in a commuting ritual, but the tacit understanding of the separation between work and domestic identities is embedded throughout our culture, and when people adopt the ritual of the commute, the familiarity of its rhythm

The commute is a classic liminal state, a period of time in which a person is betwixt and between, free of the demands of both work life and home life. The commuter engages in trans-portation, the shift between the thresholds at the entrance to the home and the office. The literal physical movement between home and office is accompanied by a mental movement as well, so that the commuter, through the ritual of the commute, becomes psychologically ready to adopt a role quite different than the one that was left behind at the beginning of the commute. The commute is a daily pilgrimage, a penitential journey in which a person comes closer to reacceptance into one identity only through the rejection of the other identity, increasing with of every mile spent on the road.

Many work-at-home arrangements operate according to a process that is commonly referred to as telecommuting. In telecommuting, the physical distance of the traditional commuting ritual is replaced by the idea that people can transcend distance through the use of electronic communications. The idea is that, through the use of the telephone, email, and other forms of electronic interaction, the telecommuter is, to all practical effect, at home and at work at the same time.

The potential for trouble in such a situation becomes apparent when one considers that, whereas a traditional commute takes place only at the beginning and end of the work day, between the work and home environments, a person is perceived to be telecommuting for the entire work day. The telecommuter, unlike the traditional commuter, never achieves a transformation of identity into a fully professional role. For the entire experience, the telecommuter remains in a liminal state, in the threshold between home and work, without being committed to the demands of either status. Telecommuters, though they may not be having an ordinary day at home, never truly arrive at work either.

Does this mean that Marissa Mayer made the right decision? Will working at home always result in poor productivity? The answer depends on how we understand productivity.

Marissa Mayer’s quantitative assessment of Yahoo employee work-at-home habits seems to support the conclusion that work at a home office won’t measure up to the standards of work at corporate headquarters. Mayer used, in her evaluation of the productivity of people working at home, the same numerical criterion as is used at the office: The amount of time spent clocked in. She looked at the number of hours employees spent logged in to the company’s computer network on their days spent working from home, compared to the number of hours logged in while physically at work, and concluded from that measurement that work-at-home productivity was unacceptably low.

The reality of Mayer’s quantitative finding cannot be contested. However, the lack of a qualitative evaluation of productivity leaves her assessment of the value of working at home seriously flawed. Mayer measured the amount of time spent at work, but she didn’t think to investigate the difference in the kind of productivity achieved through professional work that is done at home on the one hand, and the productivity that is achieved in a professional setting on the other hand.

Quantitative analysis of the sort that Mayer pursued sought to create a concrete finding by reducing the concept of productivity to a simple measure: The amount of time logged into the Yahoo computer network. A more comprehensive qualitative assessment, however, might begin with the ethnographic observation that, even in the second decade of the 21st century, not all productivity is achieved while sitting in front of an electronic screen. Not all work at home needs to be done in the form of telecommuting. In fact, given the conflict inherent in telecommuting, Yahoo employees who are working at home may be more productive when they are not logged into the Yahoo computer network.

At this point, it’s worth considering a study recently conducted by psychologists Ruth Ann Atchley, Paul Atchley and David Strayer. Their research found that a few days of separation from electronic screens, on a hiking trip, strongly increased participants’ problem solving abilities and success at tasks that required creativity. These are the sort of abilities that educated workers at a company like Yahoo need to bring to their work – and it appears that logging in to the system as usual isn’t the best way to encourage these characteristics. Time away from the ordinary office environment may just be the ticket.

When employees are required to do the kind of work that’s typical and predictable at work, it may be best for them to come in to a centralized office to devote their time to the task. Coming in to the office to work will also help cultivate a sense of camaraderie, in a shared sense of identity that’s tied to the company. Keeping work at work will also help to preserve the integrity of employees’ domestic identities.

However, from time to time, employees will find themselves feeling stuck on a problem, and unable to find a solution within their company’s standard framework. Every now and then, workers will realize that they’re beginning to rehash the same old ideas over and over again. If they’re doing important work that genuinely has the potential to advance their company’s business, people will often feel overwhelmed by the challenges that they face. When these kinds of situations occur, staying put in the office isn’t likely to help. Marissa Mayer may soon discover that keeping Yahoo’s teams at headquarters fails to bring the kind of innovation that Yahoo needs to work its way back to the forefront of online life, no matter how long workers stay on the clock.

Corporate employees probably don’t need to go hiking for days on end to find the breakthrough solutions to the problems they face at work. However, once every week or two, taking a day to not come in to the office, and not log in to the company computer network either, may be helpful… so long as there’s a method to the absence.

On these days, it won’t be a good idea to work from home, either. Home is the place where the domestic status takes over, after all. What’s needed is a third way of being, one that allows Yahoo employees to be free from the demands of both the office and the home. Accordingly, this third way needs a third place, one that has the characteristics of neither work nor home.

In such a place, employees could dedicate themselves to work, but not the type of work that they get done at the office. Employees need to leave behind their office status, and all of its conventions, if they are to come up with unconventional solutions to the challenges they face at the office. By temporarily surrendering their status, employees can access the fluidity found on the commute, and when they finally do log back in to the company network, they will return with the boon of a fresh perspective.